More than two years after the global pandemic began its epic disruption of supply chains, political and corporate leaders around the world are calling for a major redesign of globalized supply chains to emphasize security and resilience over cost and efficiency. “A new world order is emerging for the vital supply chains that deliver most of the goods we rely on for our daily existence,” wrote the Wall Street Journal’s Christopher Mims at the end of March.

“Companies, especially tech companies, are questioning the orthodoxies of the past 50 years [especially] seeking out the lowest-cost manufacturer, no matter how distant, and never carrying surplus inventory or parts.”

While this shift in mindset began before COVID-19 hit (driven mostly by the increasing geopolitical tensions between China, the U.S., and its allies), the shuddering impacts of the pandemic have heightened the pressures. Even China, the world’s largest beneficiary of globalization, seeks to lessen its dependence on exports and foreign technology with a “dual circulation” strategy that emphasizes domestic consumption and indigenous technological innovation.

Other countries and regions are focused on reducing their dependency on imports—especially advanced technology products from China. Europe calls its approach “technological sovereignty”; Japan is pursuing “strategic autonomy and indispensability,” and partnering with Australia and India on a “supply chain resilience initiative.”

The U.S. hasn’t labeled its strategy, but the direction can be seen in what Mims calls the “passel of legislation, executive orders, and rule making by the Commerce Department … aimed at shoring up domestic supply chains.”

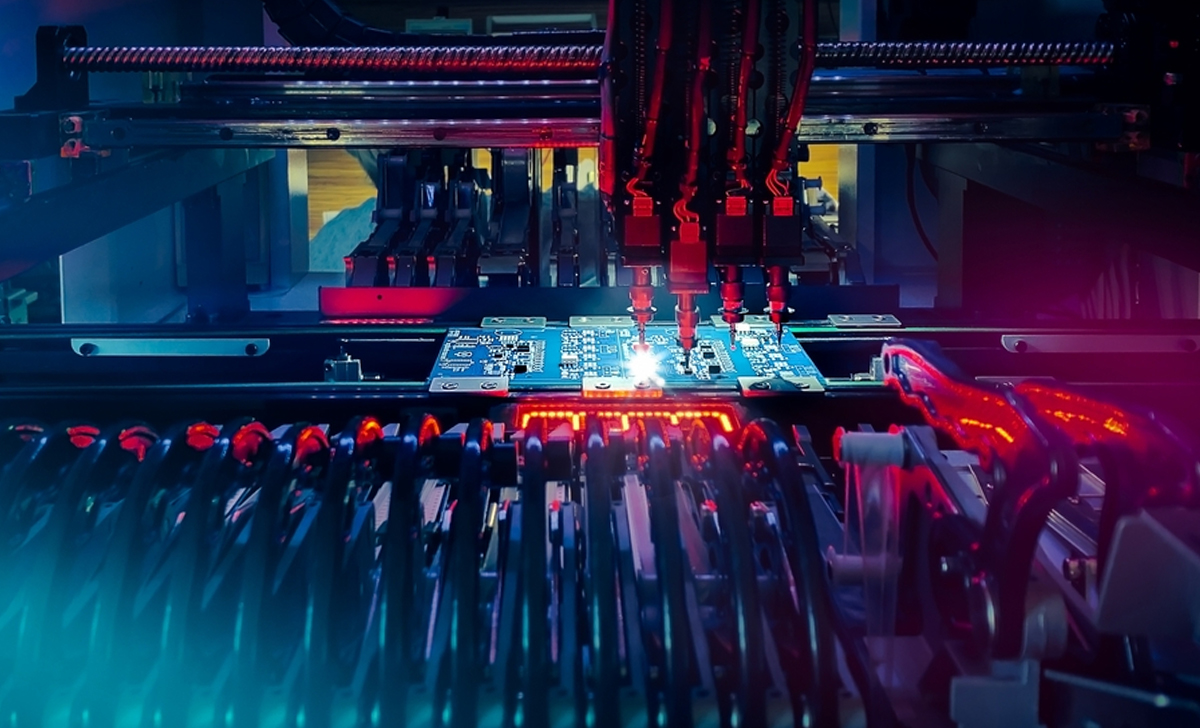

While some of these policies seek to reshore supply chains—especially for semiconductors, critical minerals, advanced batteries, and vital medicines—many policymakers recognize that skilled labor shortages and other issues will make it impossible to reshore much of the supplier base the U.S. economy relies on. “We need to harness that ‘buy American’ energy into a free-world, ‘buy allied’ framework,” said Mike Gallagher, Republican Congressman from Wisconsin and co-chair of the House Armed Services Committee’s Defense Supply Chains Task Force in a Wilson Center webinar last year.

With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—and China’s tacit support—the imperative to re-design supply chains has sharpened. “Countries are lining up in expansive geopolitical alliances separated by trade wars and actual wars [that] is reminiscent of the Cold War and even World War II,” wrote Mims, paraphrasing Klon Kitchen, an analyst with the American Enterprise Institute.”

Yet, the ultimate impact of these new and emerging resiliency initiatives is questioned by some leading supply chain experts who say that the traditional drivers of cost and efficiency won’t be shoved off the road by even the most aggressive national-interest drivers

In a Q&A posted last fall, Hitendra Chaturvedi of ASU’s W.P. Carey School of Business asked readers to think ahead three years to a day when COVID is a fading memory. Would they pay significantly more for a smartphone made domestically than they’d pay for the same product made in China? Most would not, and companies will follow the customers’ price sensitivities. “I believe that companies will do something to mitigate future risk of a pandemic, but … revenue, growth, profits, and competition will end up trumping everything else.”

Willy Shih, professor of management practice at Harvard Business School, wrote last December that no amount of subsidies for domestic semiconductor manufacturing could eliminate the need to export chips for packaging or to import tools and materials. To attain true domestic self-sufficiency in semiconductors, the U.S. would have to “relocate chip packaging, materials supplies, tool sources and much more from across Asia and Europe,” Shih wrote. “I hope we develop more domestic advanced chip manufacturing, but I think it’s unrealistic in such a complex industry where the capabilities are distributed globally to think we can do everything ourselves.”

From a European perspective, Kiel Institute economist Alexander Sandkamp told FT in January that decoupling “even partially from international supply networks … would considerably worsen the standard of living inside the EU as well as for [the EU’s] trading partners.”

And in a January commentary, Yossi Sheffi, head of MIT’s Center for Transportation and Logistics, defended just-in-time inventory practices. By enabling rapid identification of quality issues, JIT increases sales and reduces unit costs because fewer goods are returned as defective. It also “reinforces resilience because it strengthens the relationships along the supply chain [and allows] companies to react collaboratively” to risks and disruptions.

Sheffi avers that the current trend to over-order and procure buffer stock will end badly for many companies when demand drops. “The benefits of just-in-time remain just as important now as they were before today’s disruptions and should continue to guide well-designed supply chains in a post-pandemic world.”

Competing visions of the future are one of many interesting challenges that today’s supply chain managers must weigh as they plan strategies for risk management and resiliency. As Resilinc’s CEO Bindiya Vakil stated in our 2021 annual report, “there has never been a more exciting time to be in supply chain management.”