Media outlets are abuzz following a joint investigation report released by Amnesty International and African Resource Watch (Afrewatch) on January 18th titled “This is What We Die For: Human Rights Abuses in the Democratic Republic of Congo Power the Global Trade in Cobalt”. The report investigated human rights violations in the cobalt supply chain and rebuked several big brands, like Apple and Samsung, for failing to ensure that their products do not contain cobalt extracted by children in the DRC. In this post, we discuss the regulation of cobalt (or lack thereof), examine the report’s findings and discuss the potential supply chain brand risks associated with DRC-originated cobalt.

Media outlets are abuzz following a joint investigation report released by Amnesty International and African Resource Watch (Afrewatch) on January 18th titled “This is What We Die For: Human Rights Abuses in the Democratic Republic of Congo Power the Global Trade in Cobalt”. The report investigated human rights violations in the cobalt supply chain and rebuked several big brands, like Apple and Samsung, for failing to ensure that their products do not contain cobalt extracted by children in the DRC. In this post, we discuss the regulation of cobalt (or lack thereof), examine the report’s findings and discuss the potential supply chain brand risks associated with DRC-originated cobalt.

Cobalt: Not Technically a “Conflict Mineral”

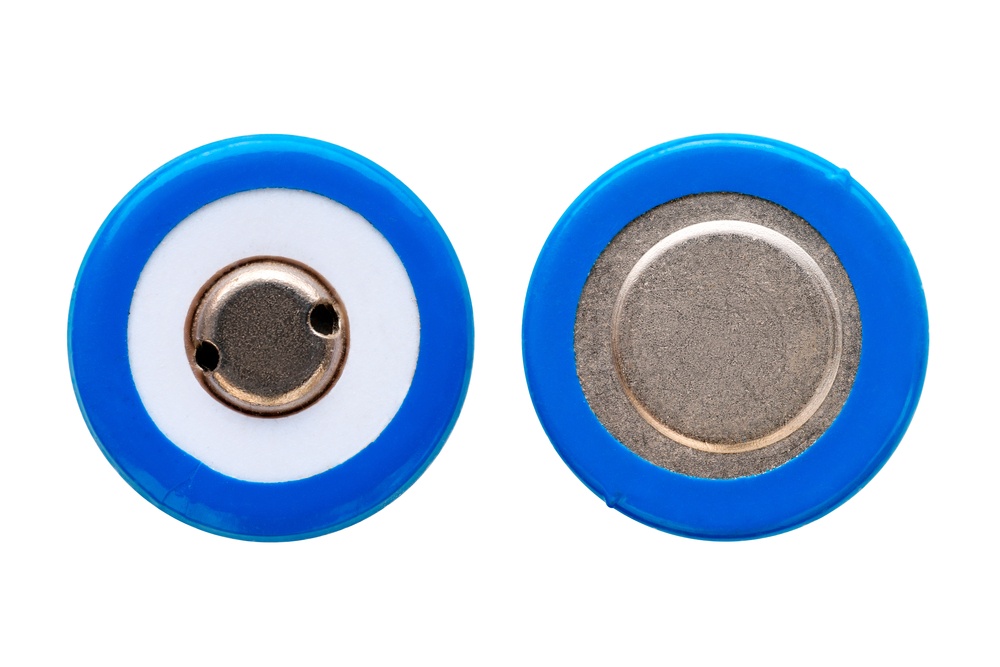

Cobalt is utilized in myriad products, particularly consumer electronics, and is an essential element in lithium-ion batteries. High demand for smartphones and the rapidly growing electric automotive industry have also stimulated demand for the metal. However, there is no regulation of the global cobalt market, which has resulted in non-governmental agencies like Amnesty International conducting comprehensive investigations to shed light on child labor in the cobalt supply chain.

Currently, cobalt does not fall under existing “conflict minerals” rules in the USA as stipulated by the Dodd-Frank Act passed by Congress. The rules require that companies disclose the use of “conflict minerals” in their products. These include tantalum, tin, tungsten, and gold – also referred to as “3TG”. The elements are mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and used in a variety of components that go into high-tech products and automobiles. The intent of the Rule is to reduce a significant source of funding for armed groups that are committing human rights abuses, including the exploitation of child labor, and contributing to the conflict in the eastern DRC.

As it is, ongoing litigation concerning key reporting and disclosure requirements has made conflict mineral compliance and 3TG transparency an industry-wide challenge.

So where does cobalt fit into all this?

It is important to note that 50% of the world’s cobalt supply is sourced from the DRC, but since it is not included in conflict minerals legislation, companies have no legal obligation to disclose their use of cobalt from the DRC.

When it comes to sourcing an industrially significant yet now controversial resource like cobalt, child labor and slave labor is a tremendous brand risk, and companies can be unwittingly implicated. Due to complex supply chains and a lack of multi-tier visibility, companies may inadvertently turn a blind eye to conditions in the supply chain until unpleasant realities confront them.

The Report’s Findings

In the report, Amnesty International detailed the unregulated, dangerous, and unhealthy conditions at the cobalt mines in the DRC. The investigation found that children as young as 7 would work in “artisanal” mines for up to 24 hours at a time without the most basic of protective equipment, such as gloves, work clothes, or facemasks to shield them from lung or skin disease. According to UNICEF, approximately 40,000 children worked in mines across the southern DRC in 2014, most of whom would work beyond twelve hours a day, carrying heavy loads to earn a pay between one to two dollars a day.

The report explains how traders buy cobalt from areas in the DRC where child labor is prevalent and sell it to Congo Dongfang Mining (CDM), a wholly owned subsidiary of Chinese mineral behemoth Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt Ltd. (Huayou Cobalt). Using investor documents, Amnesty International discovered that Huayou and its subsidiary CDM process the cobalt before selling it to three battery component manufacturers: Ningbo Shanshan and Tianjin Bamo in China, and L&F Materials in South Korea. These three component manufacturers (that bought more than $90 million worth of Cobalt from Huayou Cobalt in 2013) then sell the processed cobalt to battery makers who supposedly supply big name technology and car companies. It’s these three manufacturers that serve as the link between a long litany of consumer brands and child mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Brands Now Tasked to React

Asserting that numerous big brands have failed to do their due diligence and address human rights risks in their supply chain, the report noted 16 consumer brands that are either direct or indirect customers of the three aforementioned battery component manufacturers. Among these listed brands are big names like Apple, LG, Daimler, Microsoft, HP, Samsung, and Lenovo, to name a few.

In efforts to quell the imminent consumer and non-governmental scrutiny generated by the report, most of these brands have already released public statements addressing the allegations of transparency negligence. According to the report, Apple did not confirm or deny whether it receives components from Huayou Cobalt, but said that cobalt is among the materials for which it is conducting due diligence. Microsoft is quoted as stating, “we have not traced the cobalt used in Microsoft products through our supply chain to the smelter level due to the complexity and resources required,” but iterated that “Microsoft is fully committed to the responsible sourcing of raw materials used in [our] products” and “specifically engaged with organizations that are focused on addressing human rights issues in mining.”

A Proactive Approach

Seeing these brands frantically respond to Amnesty International’s report is understandable, and in a way, they’ve been caught in a tricky situation trying to protect their reputations. Since litigation has not required these big names to disclose information regarding their cobalt suppliers, there had yet to be a significant impetus for these companies to look further into their supply chains and verify the conditions at their cobalt suppliers. A lack of supply chain visibility and transparency effectively put them in a reactive position where they’re forced to reckon with the publicity after the fact, rather than take proactive measures to prevent such brand risks.

Given the ubiquity of cobalt in consumer goods, this report can be taken as a wake-up and a possible harbinger for future legislation. It demonstrates how important multi-tier visibility is in identifying potentially harmful cogs throughout their supply chains. Brand risk management should be taken as seriously as general supply chain risk management because, in many regards, reputation is everything in a fiercely competitive global marketplace. Companies shouldn’t have to wait for legislation to inform their corporate social responsibility (CSR) perspective, but rather, should look ahead. Amnesty International’s report not only reminds companies of the importance of up-to-date CSR reporting, but also the importance of developing deeper relationships with their suppliers. Utilizing supply chain network mapping services help companies develop a more transparent and manageable supply chain and avoid potential brand risks.